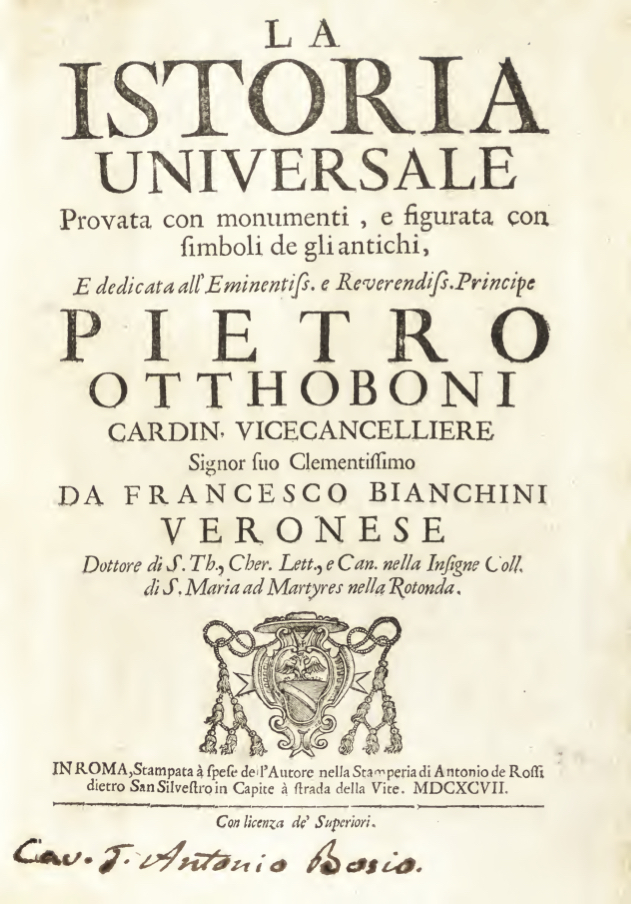

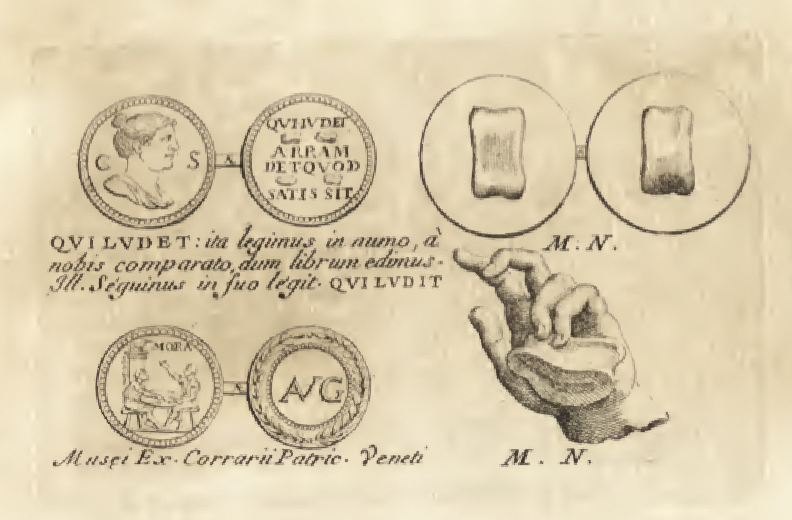

Bianchini, La istoria universale provata con monumenti e figurata con simboli de gli antichi

Francesco Bianchini (13 December 1662 – 2 March 1729) was an Italian philosopher and scientist. He worked for the curia of three popes, including being camiere d’honore of Clement XI, and secretary of the commission for the reform of the calendar, working on the method to calculate the astronomically correct date for Easter in a given year.

Bianchini was born of a noble family at Verona, the son of Giuseppe Bianchini and his wife, Cornelia Vailetti. In 1684 he went to Rome, and became librarian to Cardinal Ottoboni, who, as Pope Alexander VIII (1689), raised him to the offices of papal chamberlain and canon of Santa Maria Maggiore. Clement XI sent him on a mission to Paris in 1712, and employed him to form a museum of Christian antiquities. A paper by him on Giovanni Domenico Cassini’s new method of parallaxes was inserted in the Acta Eruditorum of Leipzig in 1685.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in January 1713 after being proposed by Sir Isaac Newton.

A gnomon in the south wall of the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri projects the sun’s image onto Bianchini’s line every solar noon

His deduction of the rotational period of Venus was based on the observation of its surface using a 2.6″ (66mm) 100-foot focal length aerial telescope. Today, we know that this is impossible, because of the thick cloud cover on this planet. He also worked on the parallax of Venus, and he measured the precession of the Earth’s rotational axis.

As part of his efforts to improve the accuracy of the calendar, Bianchini was commissioned by Pope Clement XI to construct an important meridian line in the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri (the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels and the Martyrs) in Rome, a device for calculating the position of the sun and stars.

According to a Catholic News Service online news story by Carol Glatz from 5 August 2011, Pope Benedict XVI noted this when he explained the importance of astronomy- especially when clocks were primitive and prone to error- in the determination of certain liturgical celebration days and the times for certain daily prayers, such as the Angelus.

His point of view on the Copernican system is not evident, but it was noted that the picture of the planetary system in his book about Venus has an empty centre. Craters on Mars and the Moon are named in his honour. He also worked as a topographer and archaeologist of ancient Rome, and as a collector.

In 1726, near the Via Appia, a structure consisting of three sepulchral chambers of some of the servants and freedmen of Augustus and his wife Livia were discovered and excavated. Bianchini explored these rooms and published a description. One day in 1727, while exploring the ruins of the palace of the Cesar’s, on the Palatine Hill, he fell through the ceiling of a vault and was severely injured.

Download

Bianchini_La istoria universale provata con monumenti e figurata con simboli de gli antichi.pdf